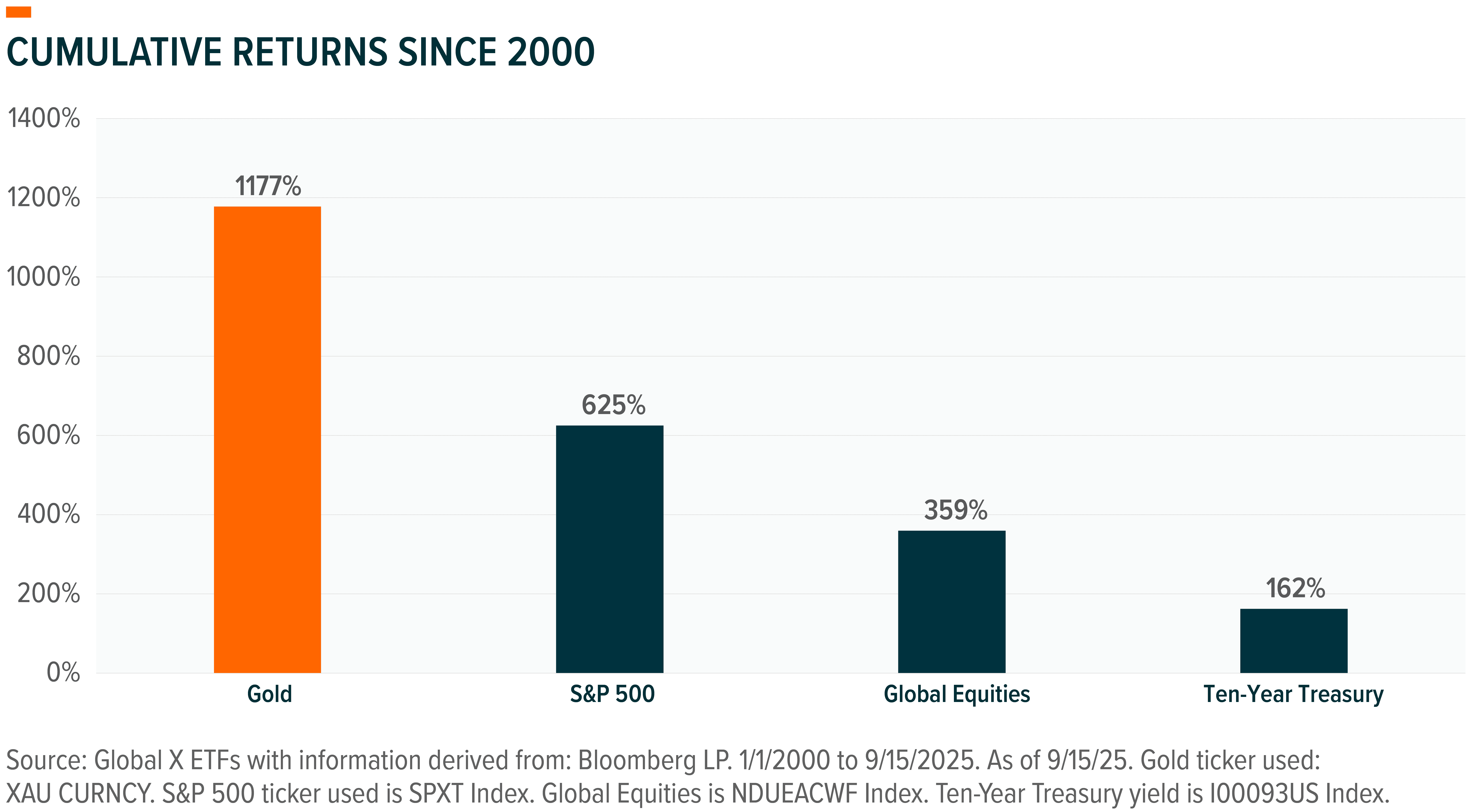

Gold’s ascent to new all-time highs has been nothing short of remarkable, outperforming both U.S. and global equities since the turn of the century.1 We see the rally driven by a fundamental change in demand, underpinned by robust central bank purchases. We believe this incremental allocation shift towards gold remains very much in the early innings, with the bullion once again becoming the dominant reserve asset.

Key Takeaways

- Rising geopolitical tensions, widening imbalances, and a worsening debt outlook point to gold playing a more important role in the global economy.

- Gold is on pace to supplant U.S. Treasuries as the world's dominant reserve asset, placing the bullion once again at the heart of the global monetary system.

- Despite its incredible performance over recent years, gold prices may have more room to run if price insensitive central banks continue to diversify their reserves into gold.

Gold’s History as a Reserve Asset

Central bank reserves help countries ensure credibility and liquidity. They also represent an important gauge into the monetary and financial health of a country. Under the current monetary system, central banks have therefore historically mainly reserved U.S. Treasuries (given the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency) and gold. Gold’s long and unmatched track record as a store of value, underscored by the fact that a Roman Centurion’s salary paid in gold during the reign of Emperor Augustus roughly equates to the compensation of a U.S. Army Captain with six years of experience today, as well as its liquidity, scarcity, and lack of real economic utility highlight the attractiveness of gold as a reserve asset.2 However, despite its unmatched track record, gold’s role in the global monetary system has changed drastically over the previous century.

Gold was the primary reserve asset, be it directly or indirectly through currency convertibility, from the turn of the twentieth century until President Nixon severed the link between the USD and the precious metal on August 15, 1971. Nixon’s unliteral move effectively placed U.S. Treasury debt at the heart of the global financial system and began the modern era of fiat currencies. This had a large impact on global trade, with trade surpluses now being reinvested into U.S.-dollar denominated assets and in turn creating a structural demand for the world’s reserve currency. This added driver of dollar strength made U.S. exports less attractive and incentivized imports. This growing trade deficit translated into higher levels of capital being recycled in the U.S. and in turn a stronger dollar, ultimately creating a reflexive cycle that led to fundamental shifts in the U.S. economy. However, growing fiscal and geopolitical concerns have broken this trend over recent decades, with gold set to surpass U.S. Treasuries as the main reserve asset, potentially placing the bullion once again at the heart of the global monetary system.

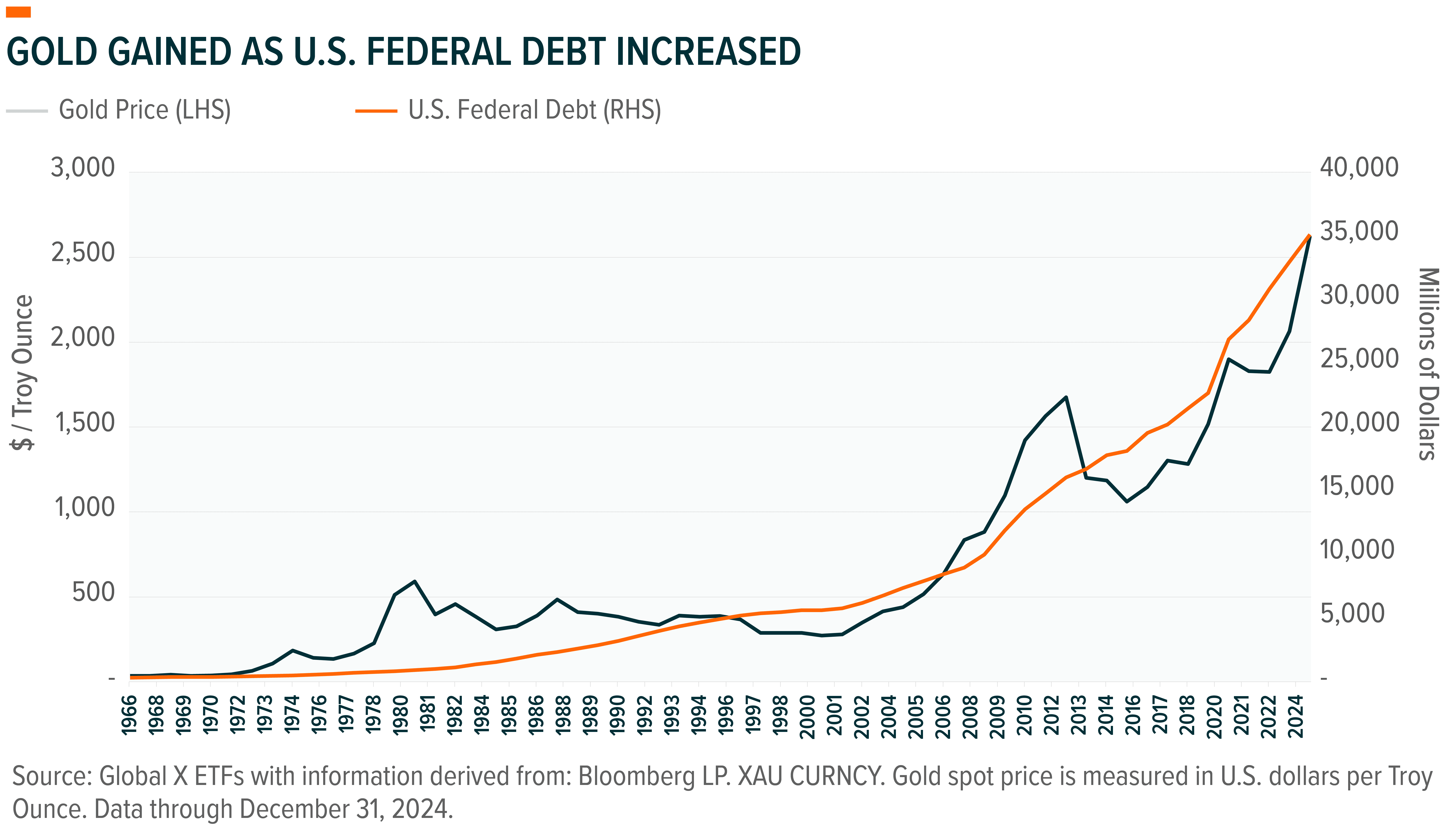

Why is The Debt Outlook Pushing Central Banks Towards Gold?

The combination of the post 1971-monetary system (which requires the U.S. to run trade deficits to provide dollar liquidity to the world), demographics, and increased fiscal spending drove a sharp rise in the U.S. debt level, with the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio rising from 35% in 1970 to 124% at the end of 2024.3 Given the growing interest burden and worsening demographics, this situation is projected to deteriorate further, with the Congressional Budget Office forecasting debt to GDP to rise to over 155% by 2055.4 Although this trend of growing indebtedness is occurring globally, the United States is in a unique situation given it possesses the world’s reserve currency, reducing the risk of nominal default. Therefore, we believe the increased allocation to gold has been driven by growing concern around the real value of debt, with the probability that governments around the world will have to inflate nominal growth to meet their obligations increasing.

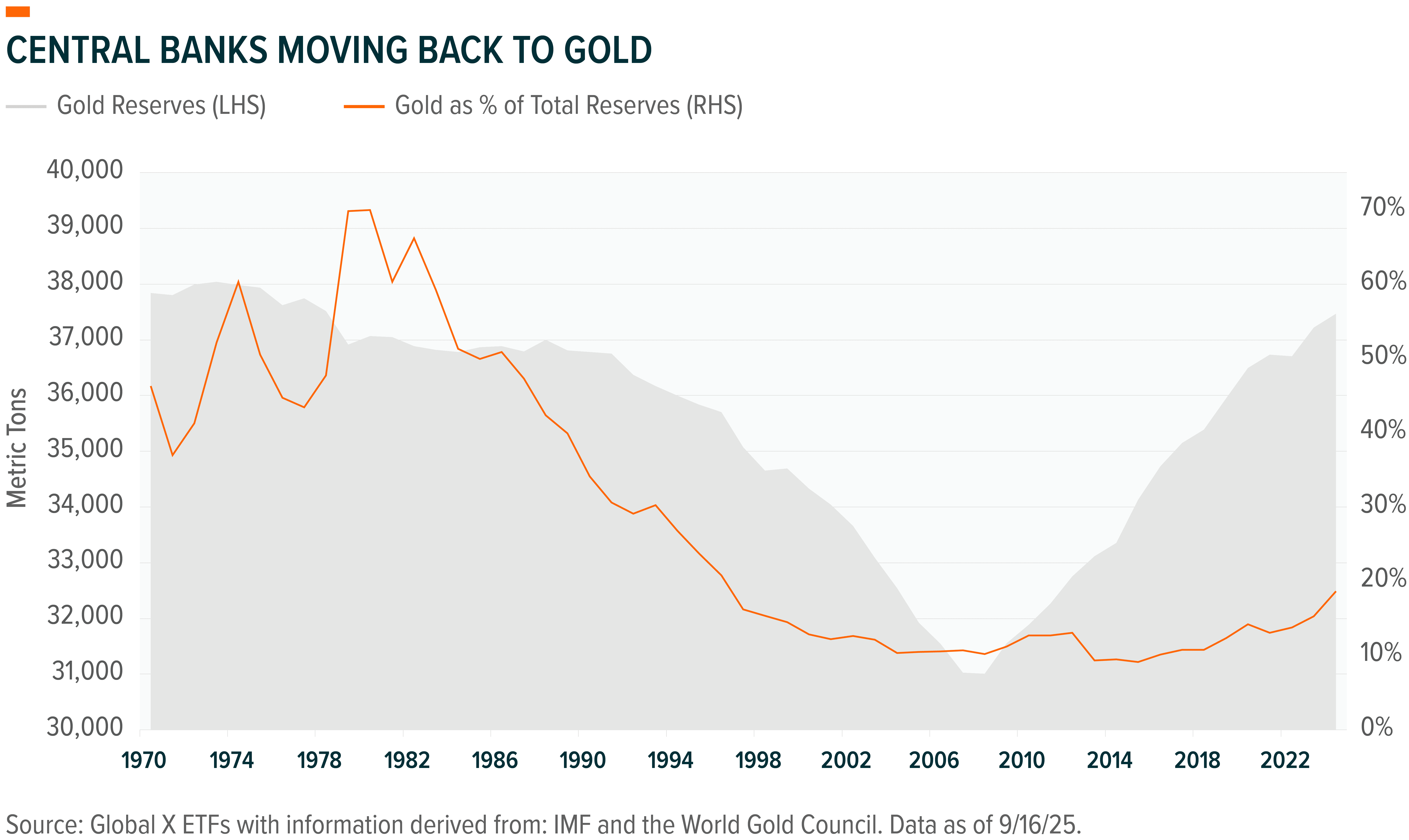

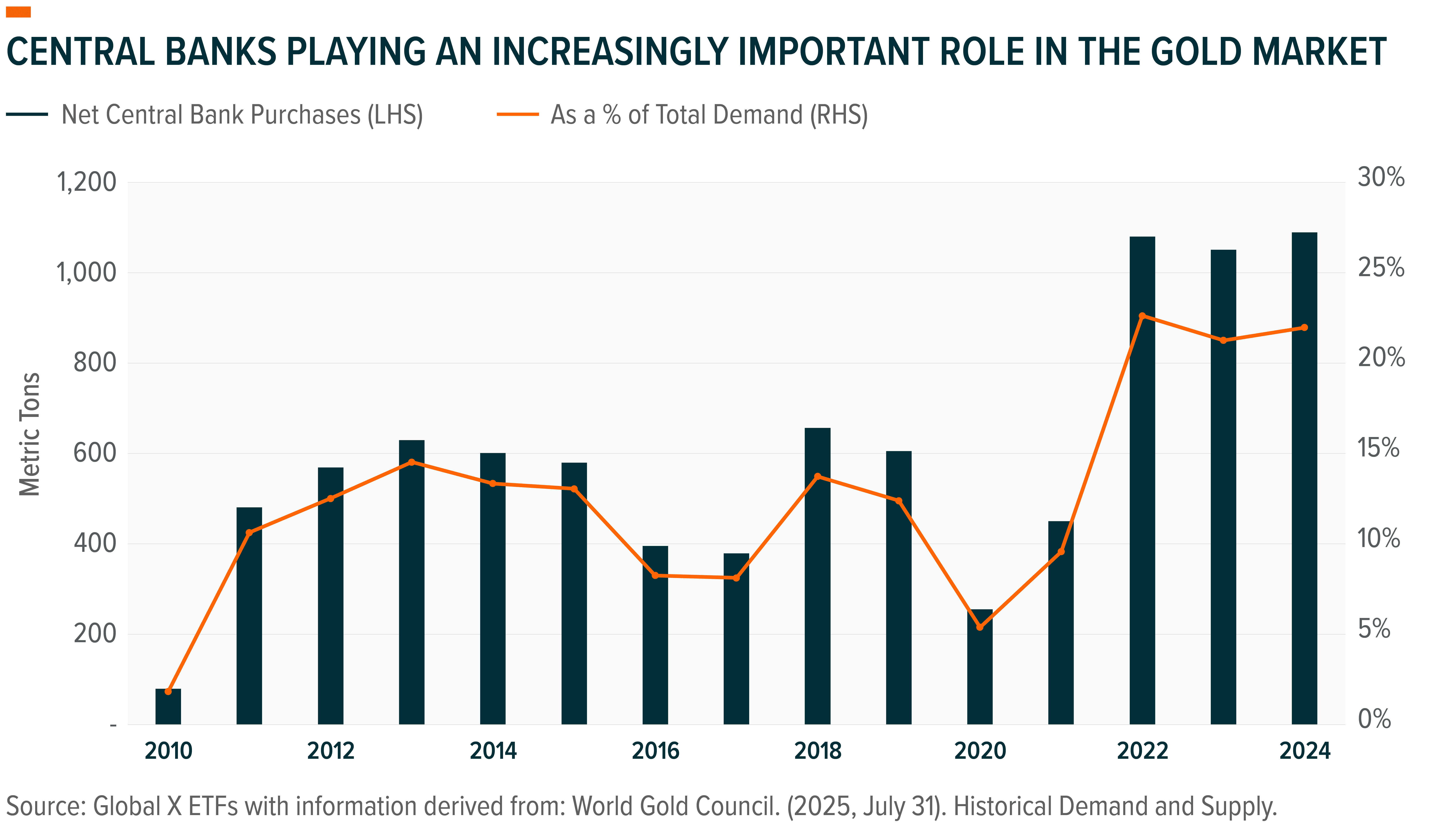

This shift to gold began shortly after the great financial crisis, a period characterized by an explosion in the money supply, rising levels of indebtedness, and asset price inflation. Central banks responded by incrementally allocating to gold, with the bullion being the logical alternative to debt given its liquidity and stable track record. This trend has continued, with central banks buying gold every year since 2010.5 Looking ahead, we believe we are in the early innings of this shift to gold, with gold as a percentage of central bank reserves sitting at 19% at the end of 2024, well below the post-Bretton Woods average and high of 29% and 70%, respectively.6 Additionally, we don’t see the main driver of this shift changing, with debt to GDP set to increase as governments globally show little political will to aggressively cut fiscal spending or the ability to raise revenues, further increasing the probability of higher real returns for gold relative to sovereign debt.

Why Did Central Bank Gold Purchases Inflect in 2022?

The shift to gold hit an inflection point earlier this decade, with the volume of central bank purchases of the bullion rising 140% year over year in 2022 to over one thousand metric tons.7 This sharp acceleration began with the seizure of Russian reserves following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This served as a catalyst for other countries, especially those with less geopolitical alignment with the West, to protect their countries’ wealth against confiscation by taking physical delivery of gold. This is particularly evidenced by the People’s Bank of China having been the largest purchaser of the bullion since 2022.8 Looking ahead, we see today’s elevated levels of global geopolitical tensions supporting an incremental shift to gold as a reserve asset. This acceleration in the shift to gold by central banks also coincided with a sharp spike of persistent inflation, making us believe that geopolitical risk is not the root cause of the shift to gold. Rather, we think security concerns acted as an accelerator to an ongoing trend that began over a decade earlier. This is evidenced by central bank purchases remaining above one-thousand metric tons in both 2023 and 2024.9 Nevertheless, we highlight that these events once again proved gold’s utility as a secure, liquid, and effective store of value.

Gold Reemerging as the Dominant Reserve Asset

We believe global central banks remain in the early innings of diversifying their reserves into gold. If true, the increased presence of a consistent and price-insensitive buyer could further support gold prices moving forward. Both the worsening global debt outlook and growing geopolitical uncertainty underscore our view that we remain in the early stages of this shift, with gold being the logical substitute for debt given its long-standing presence on central bank balance sheets, its extensive track record as a store of value, and its growing market size and liquidity. Global central banks have also indicated their intention to continue buying, with 76% of these groups indicating that their gold reserves will increase over the next five years.10 It is also important to highlight that even as central bank’s shift their reserve allocation to gold, the U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency has not diminished, with the dollar cemented as the means of exchange while gold remerges as the store of value.

Conclusion: Gold To Play a More Important Role in an Increasingly Uncertain World

Rising geopolitical tensions, widening imbalances, and a worsening debt outlook point to gold once again playing a more important role in the global economy. Its reemergence as the dominant reserve asset could disrupt one of the major macro trends of recent decades: reinvestment of trade surpluses in U.S. Treasuries. Reduced demand for U.S. assets would likely weigh on the relative strength of the U.S. dollar, not only easing debt burdens for many countries in local currency terms but also giving central banks more flexibility to loosen monetary policy, stimulating growth and potentially lowering global debt-to-GDP ratios over time. A weaker dollar could incentivize U.S. exports, improving their cost competitiveness as well as boosting global purchasing power. Ultimately, gold’s renewed role as a reserve asset may help rebalance trade worldwide, marking a sharp departure from the post-1971 system. If one thinks that geopolitical tension could rise, the world is moving to a period of isolationism, and that governments need to spend their way out of debt, then gold is an asset class that can benefit from each and all of these scenarios.