Six months after the White House unveiled a tariff schedule for global trading partners, this seems like a good time to check in on the state of play. The initial announcement on April 2 sent equity markets sharply lower, but a week later, on April 9, markets calmed as the White House put many tariffs on hold to allow for negotiations with major trading partners.1 Despite lingering concerns that tariffs would slow international trade and drag the global economy since then, both the S&P 500 and the MSCI World indexes have advanced by more than 20%.2

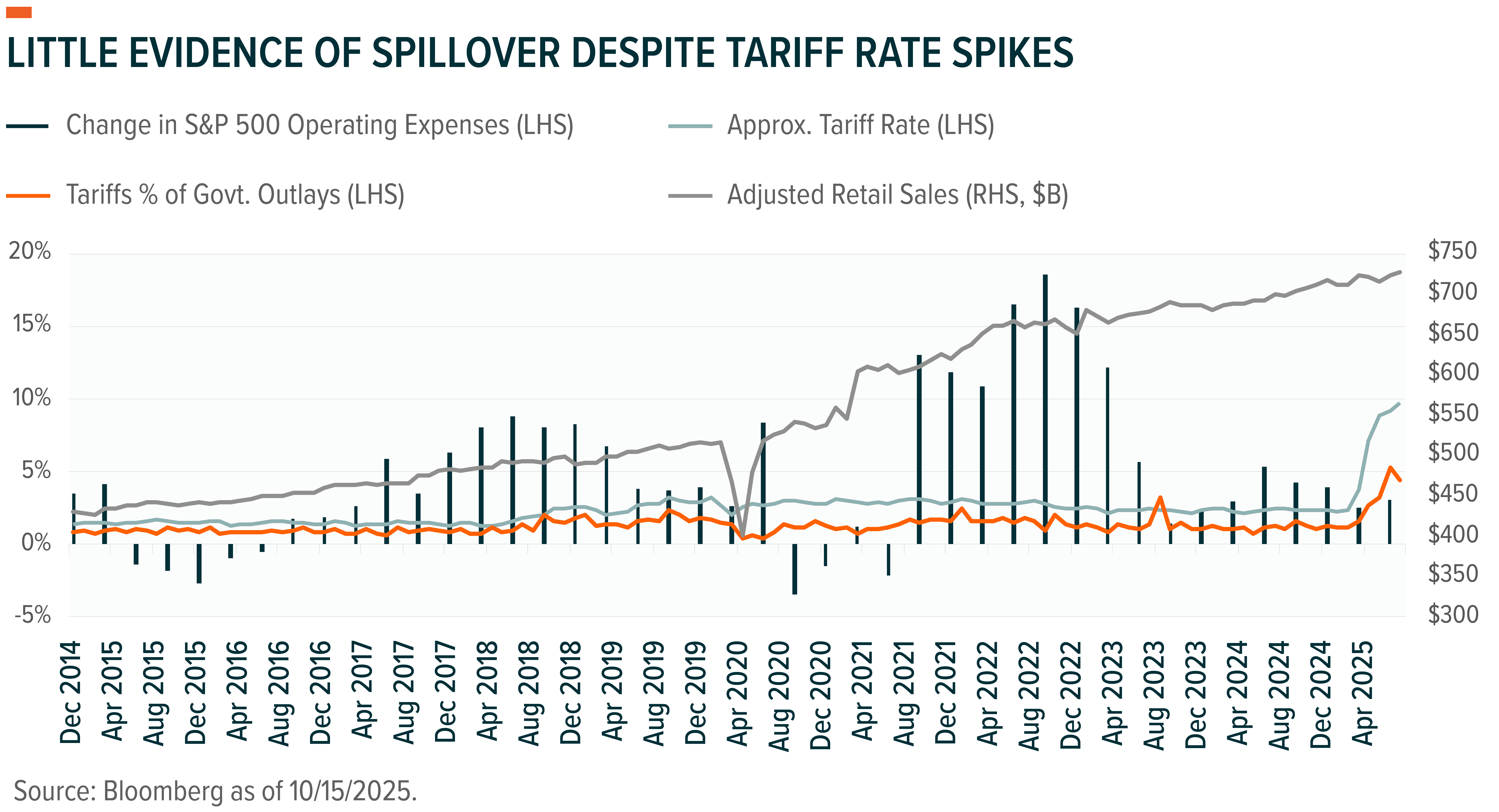

While tariff rates have increased markedly, government revenue from imports in the second quarter was only 0.2% of GDP, close to the 0.3% base case that we outlined in our 2025 Outlook.3 With only modest evidence of adverse impacts from tariffs, strong fundamentals for large-cap companies and the steady upward march in asset prices suggested that investors had moved on from the tariff risks. But that notion was seemingly shattered on October 10 when the White House hinted at the possibility of significant tariff increases on China and equity markets moved lower.4

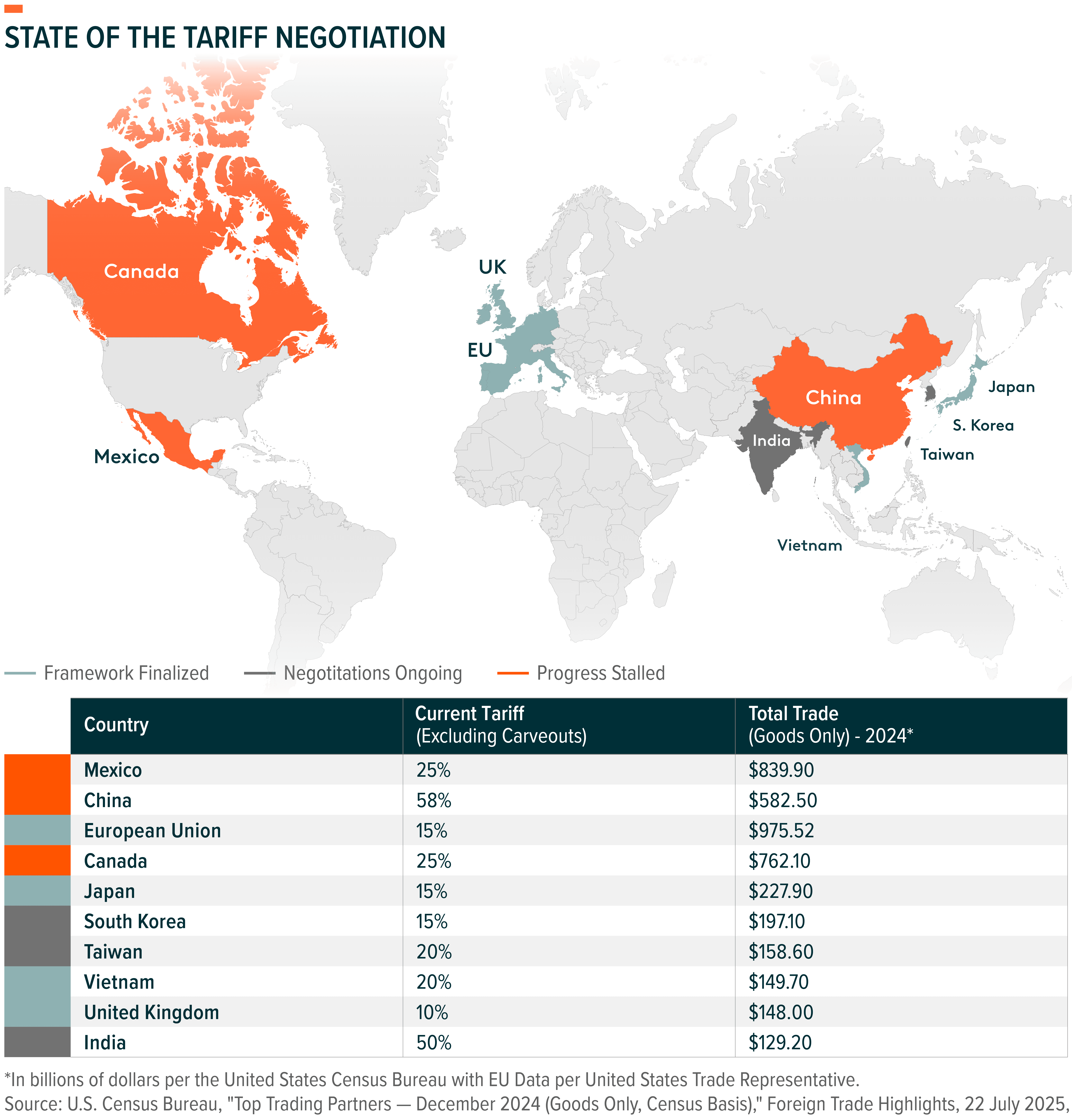

The Treasury and Commerce Departments negotiating with the U.S.’ major trading partners have made progress, but thus far it’s a patchwork of agreements and announcements. So, in this piece, we aim to provide a one-stop tariff shop, looking at the aggregate impact, details about agreements with the U.S.’ top 10 trading partners, and potential implications across the economy, markets, and investment themes.

Key Takeaways

- The jump in tariff rates drove a meaningful increase in custom duty receipts, but the net economic impact remains relatively modest.

- While almost all top trading partners are subject to higher tariffs, a wide range of deals and exemptions makes the landscape highly heterogenous.

- Certain industries seem poised to fare better than others. High-tech products, for example, has been largely excluded from many of the import duties, while industries relying on commodity imports look more vulnerable.

Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on the Economy

Tariffs can impact the economy in numerous ways. For starters, tariffs function as a tax that shifts money from the capital-efficient private sector to the less-efficient public sector, creating a drag on capital’s productivity. They also raise costs for businesses, potentially threatening profit margins and earnings. Where possible, businesses will eventually look to pass on those costs through higher prices, which can dampen consumer demand and spending. So far, corporate profitability and consumer demand remain reasonably robust, but there are signs that the labor market and possibly the broader economy are slowing as new tariff policies are implemented.5

The actual increase in government revenue from imports has stepped up meaningfully in recent months. In January 2025, tariffs accounted for $7.3 billion of government revenue. By August, that number was $27.7 billion, an almost fourfold increase.6 The approximate tariff rate increased from 2.2% to 9.7%. At the start of the year, tariffs were about 1.1% of government outlays. By July, they were 4.4%, which is a relatively big gain in a short period, though the net impact on the economy is pretty modest. The government raised $64.4 billion in Q2 2025 on GDP of $30.5 trillion, thereby accounting for only about 0.2% of GDP.7

To date, there is little evidence that tariffs have adversely affected consumers or businesses at scale. August U.S. retail sales grew 5.0% year-over-year (YoY), averaged 4.4% growth since April and above the average growth since 2000 of 4.2%.8 Second-quarter personal consumption grew 2.4% from the prior year and is also above the 25-year average of 2.2%.9 Corporate operating expenses have also remained reasonably subdued. The White House has seemingly figured out a way to increase taxes modestly without Congress having to vote on the matter.

Manufacturing and construction employment remain weak. Three-month rolling averages show that jobs in both sectors have been declining since the White House’s April announcement, which is interesting because tariffs are designed, in part, to protect domestic jobs.10 Labor weakness is probably the biggest risk to the economy at present, and the Federal Reserve has noted rising risk in employment.

You Gotta Tariff Someone

Below, we break down the complex tariff landscape for the U.S. and top 10 trading partners, which together account for approximately 80% of U.S. imports.11 Negotiations are at varying stages, with tariff rates ranging widely, from 10% to 58%, and various carveouts included in many of the deals.

European Union (EU): A framework is in place, but a final agreement remains uncertain. Many different interests are at play given the economic differences across member states. The current framework calls for reducing auto tariffs on U.S. imports from 27.5% to 15%, while the EU must eliminate tariffs on all U.S. industrial goods, including autos, which are currently subject to a 10% tariff.12 The U.S. has increasingly focused on rules that could adversely impact U.S. tech companies, and more recently the U.S. sought exemptions on climate and corporate compliance rules. The steel and aluminum 50% tariffs still apply, while pharmaceutical and semiconductor imports are capped at 15%.13

Mexico: The U.S. and Mexico are negotiating with the first six-year review of the U.S-Mexica-Canada trade deal (USMCA) coming up in 2026. The current tariff rate is 25%, but it is set to rise another 5% after the end of a 90-day pause expiring November 1.14 That said, all goods that comply with the current USMCA terms are duty free, which account for most of the imports. A new tariff set for November 1 applies to medium- and heavy-duty trucks, as import volumes have tripled since 2019.15 Section 232 tariffs, imposed in the name of national security under the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, are in effect at 50% for steel, copper, and aluminum.16 In the current scenario, more than 80% of goods might not be subject to the tariffs.

China: The negotiations between the U.S. and China are very delicate and the source of continued market angst. Prior to the current round of negotiations, there was a 25% tariff on approximately 65% of the imports from China.17 The U.S. has moved to close loopholes such as the de minimis rule so that tariffs apply to 100% of imports. Rates have also been raised, including an additional 10% reciprocal increase and another 20% tied to fentanyl, bringing the effective tariff rate to roughly 58% on Chinese imports versus 33% on U.S. exports.18 The current pause is set to expire on November 10. Adding complexity to these negotiations is that they also encompass intellectual property, technology transfer, market access, rare earths, and geopolitical allegiances.

Canada: The relationship between the U.S. and Canada has deteriorated since the start of the year, and negotiations seem stalled. Canada has generally adopted a tit-for-tat strategy in response to U.S. tariffs of 25%.19 Canada responded with tariffs on the non-North America parts of imported cars. Canada has taken a more measured approach to materials and natural resources, even after the 50% tariffs on steel and aluminum. The U.S. is expected to drop tariffs on USMCA-compliant goods.20

Japan: The U.S. and Japan reached a trade agreement that is reasonably straightforward. Rather than follow a sector-based template like in other negotiations, the U.S. will apply a 15% tariff on most goods, including autos, which were previously subject to a 25% rate.21 The agreement includes $550 billion of pledged capital investment in the U.S. through loans and guarantees. Japan also agreed to buy an additional $8 billion in agricultural products and increase rice imports by 75% above the existing quota.22 Reducing non-tariff barriers has generally helped improve U.S. export volumes. The agreement does not cover pharmaceuticals and semiconductors, which will likely be negotiated later.23

South Korea: The U.S. and South Korea hope to finalize a deal by the end of October. The current framework calls for a 15% tariff, below the 25% rate announced on April 2.24 It includes no tariffs on U.S. exports. Autos represent about a quarter of U.S. imports from South Korea. Sensitive product areas such as computer chips, batteries, machinery, and pharmaceuticals are currently excluded.25 Copper, steel, and aluminum will be tariffed at 50%, while South Korea will have carveouts on U.S. beef and rice exports. The framework also calls for $350 billion of South Korean investments in the U.S. through loan guarantees, including $150 billion for shipbuilding and $100 billion for liquid natural gas (LNG).26 Negotiations have stalled over these terms, with South Korea looking to hedge currency risk through a bilateral currency swap and the U.S. looking for cash and equity investment rather than loans.27

Taiwan: The U.S. initially proposed a 32% tariff rate, but it is currently at 20%, with negotiations ongoing and Taiwan aiming for a lower rate.28 At present, semiconductors and electric goods are exempt from the tariff, which largely applies to machinery and plastics. The U.S. also imports items such as screws, bolts, nuts, motor vehicle parts, electrical transformers, and power supplies that are subject to current tariff rates.29 U.S. imports from Taiwan have been growing much faster than exports, an imbalance that the U.S. wants to change by bringing 50% of semiconductor manufacturing onshore.30 Taiwan Semiconductor pledged a $165 investment in a U.S. facility, and there is a proposal for a $10 billion increase in U.S. agricultural exports over four years.31 The U.S., however, seeks a more comprehensive investment plan.

Vietnam: The U.S. currently has a 20% tariff on imports from Vietnam and a 40% rate on goods shipped through the country to deter manufacturers attempting to mask the origin.32 These rates are below the April 2 figure of 46%. Vietnam is opening its market to U.S. goods with no tariffs. On the other side, the U.S. is Vietnam’s largest export market, with computer parts, machinery, appliances, clothing, shoes, and other consumer goods the top products.33 The U.S.’ trade deficit with Vietnam is particularly high, running over $100 billion per year.34 Copper, aluminum, and steel will be tariffed at 50%.

United Kingdom (UK): The U.S. runs a trade surplus with the UK and exports about $80 billion in goods.35 A trade deal that sets the U.S. tariff rate at 10% is in place, but it has some interesting features. For example, UK auto exports will be charged the 10% rate up to 100,000 units, and then a 25% rate on any additional vehicles.36 UK steel is only subject to a 25% tariff, below the 50% for most countries, but copper imports are charged the higher rate. The deal also includes provisions for $700 million in U.S. ethanol exports and $250 million in agricultural products such as beef.37

India: The U.S. and India have struggled to reach an agreement, despite a historically good relationship between the leaders. The U.S. imposed 50% tariffs on Indian goods as of August 27, in part as a penalty for India purchasing Russian oil purchases.38 Previously, the tariff rate was 25%. The U.S. is India’s largest export market, approximately three times larger than its next trading partners. The higher tariff rate could meaningfully reduce U.S. imports from India and affect industries such as jewelry, textiles, footwear, carpets, and agricultural goods.39 Imports of electronics, pharma, energy, and critical mineral exports are currently exempt.40 India has typically resisted opening their market to U.S. agricultural goods, which has been a challenge in negotiations.41

Guess That’s Why Some Sectors Will (and Will Not) Call It The Blues

The tariff impact will not be uniform across sectors and industries. In the end, certain areas are likely to be harder hit, while others manage to operate relatively unscathed.

Two areas that seem relatively insulated from the tariff battle are services and high-tech products. The service sector has been notably excluded from tariff discussions, which have focused almost entirely on the cross-border movement of goods. The U.S. exports more than $1 trillion in services annually, making it the largest service exporter in the world.42 Operating expenses for service businesses could rise modestly from input price increases, but a major shift in demand at home or abroad is unlikely.

Carveouts for high-tech products such as semiconductors and memory chips suggest sensitivity around technology tied to the AI buildout and productivity enhancements. The U.S. has long relied on foreign imports of products like semiconductors, and the CHIPS Act of 2022—which provides public subsidies for onshoring tech manufacturing— underscores the challenges of redirecting both demand and production.43

Taken together, tariffs may be less of a concern for tech services companies. AI companies are some of the biggest beneficiaries of U.S. efforts to ensure supplies of necessary components and to potentially limit others’ access to premium technologies. Cybersecurity firms provide services to clients across the globe, and their biggest exposure to the trade conflict is ensuring sufficient access to compute capabilities. The story is similar for cloud computing companies.

Social media and fintech are interesting segments to examine because they provide services that are not subject to tariffs, but they may be sensitive to a slowdown in consumer activity should tariffs erode confidence in the labor market.

Domestic producers of copper, steel, and aluminum may be well positioned to benefit from Section 232 tariffs. The White House first announced 25% rates on steel and aluminum in February, subsequently increasing them to 50% in July. Then the administration announced 50% tariffs on copper imports in July.44 U.S. materials and commodity companies focused on the U.S. market, including areas such as infrastructure development, could see demand increase given the higher cost of international goods and realize some improved pricing power. Copper producers could benefit given the combination of data center buildouts and global demand from infrastructure.

Another industry potentially well positioned is U.S. natural gas and its support infrastructure, such as pipelines. The U.S. is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, which may be a focus for negotiators aiming to reduce trade imbalances. Daily U.S. exports of natural gas increased from around 43,000 metric tons in 2017 to 297,000 in 2025, an almost 700% increase.45 While domestic demand remains strong amid rising electricity needs, growing foreign demand may be another source of revenue.

Some industries are likely to absorb a higher share of costs, and their ability to pass price increases to customers may vary. Retailers, for example, may well get pinched given the heavy reliance on imports in the consumer goods market. Recent reports show little evidence of significant price increases, potentially suggesting intense competition and slowing demand have limited retailers’ pricing power.46 Third-quarter sales and profit margins are likely to offer better insight now that tariffs have been in place for some time.

Another segment potentially facing headwinds in the near term are industrials that rely on physical inputs like natural resources. With 50% tariffs on copper, steel, and aluminum tariffs, costs for auto and heavy equipment manufacturers could rise meaningfully.47 Materials tied to items such as fasteners and electrical equipment could also weigh on profits. B2B industrials may be better positioned to pass higher costs on to customers than consumer-facing firms. That said, companies at the forefront of innovation in areas such as robotics and automation may have an easier time sustaining margins.