Software has become the market’s latest AI-disruption punching bag. The concern is simple: if AI agents can complete tasks end to end, they could compress human labor, reduce the need for “middle-layer” software, and weaken moats as the cost of building new tools falls toward zero. That has direct implications for the terminal value assumptions embedded in high-growth software multiples.

We think the market is right about the pressure AI creates for software, but wrong about the conclusion. AI will likely reshape business models across parts of application software, but it also makes software more critical, because it is the control layer that embeds AI into workflows, helps manage agents, and connects AI models to enterprise data.

This piece breaks down the ongoing dynamic, maps business models prone to disruption, and highlights early areas where durable winners are likely to emerge, including AI enabling software and cybersecurity.

Key Takeaways

- AI won’t wipe out all software, but it is likely to drive dispersion.

- Seat-based applications with shallow workflow integration and weak data moats face the greatest disruption risk.

- Software companies tied to the AI development ecosystem and cybersecurity could prove to be relative beneficiaries of the same forces driving the selloff.

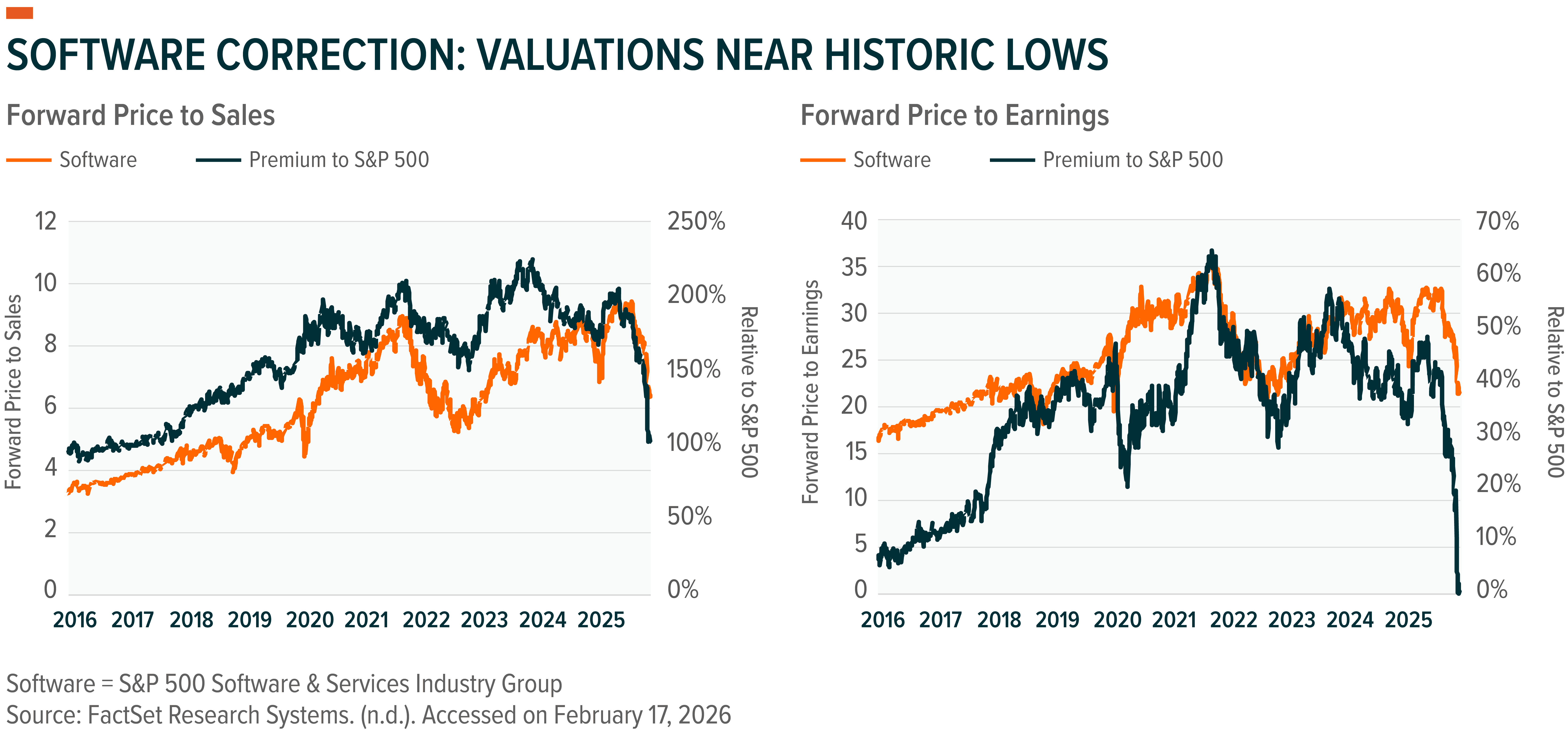

Market Likely Mispricing Software Risk

The threat of AI-led disruption has triggered a broad sell-off in software, with nearly $1 trillion in equity market cap erased in a matter of few days.1 While this fear has been building for a while, it accelerated after the launch of Anthropic’s Claude Cowork earlier this year, a desktop agent that automates work across files and tasks.2 The market’s read is simple: if agents can execute workflows end to end, then layers of software solutions in the middle become harder to justify, compressing budgets and hurting a range of companies in the process.

We agree there is some risk here. In the age of AI, seat-based pricing is the most exposed model because it ties revenue to the number of users. If agents can complete tasks autonomously, IT buyers will test whether smaller teams can maintain output, then push to cut seats or renegotiate pricing. That weakens recurring revenue visibility and forces a reset in long-duration valuation assumptions around software.

But, in our view, the market is also widely overgeneralizing. Not all software is sold per seat, and that mix has been shifting for years. As far back as 2021, roughly 41% of software was priced seat-based, while usage-based models were already gaining prominence.3 That share has likely only declined since.4 We also think it’s a mistake to assume all software needs to serve as the primary user interface. A large and growing share of the industry focuses on infrastructure tooling, such as databases, observability, orchestration, and security, which does not compete with AI applications but instead powers and manages them.

The other concern is that AI simplifies software creation and pushes the marginal cost of making a tool toward zero. If anyone can spin up an app, does that pressure enterprise renewals and ultimately erode the terminal value of some vendors? Again, we see risk, but it’s likely concentrated in specific areas. Software with shallow workflow integration and limited proprietary advantages is more exposed. That includes many horizontal productivity tools, which were already experiencing pricing pressure even before AI accelerated that trend.

That said, while creating software is getting easier, replacing it at scale is still extremely difficult. High switching costs, embedded data and workflows, and services-heavy implementations create durable barriers. These advantages may not be obvious in a product demo, but they are often deciding factors in enterprise buying and renewal behavior. High implementation inertia compounds, and that is the real moat.5

Rather than a broad collapse in long-term value across software, the more realistic outcome is divergence. Pressure is likely to concentrate on seat-based, single-purpose tools and easily replaceable horizontal platforms. At the same time, spending should shift towards systems that grow with usage, are monetized via measurable outcomes, and support more complex workflows.

The buildout of AI-native platforms and vertical agentic solutions should also expand the overall software surface area, even as it reshuffles who captures the economics. This pattern isn’t unique to software. Across tech and the broader economy, AI is concentrating value among the companies that enable it, while older, less differentiated parts of the ecosystem face margin pressure and reduced investment.

In software, enterprises may buy fewer generic seat licenses, but they will likely continue investing in the systems that connect models to data, govern agentic actions, enforce security. The post-selloff setup looks more like a sorting event than a sector unwind.

The Structural Reality: Software Spend Is Accelerating

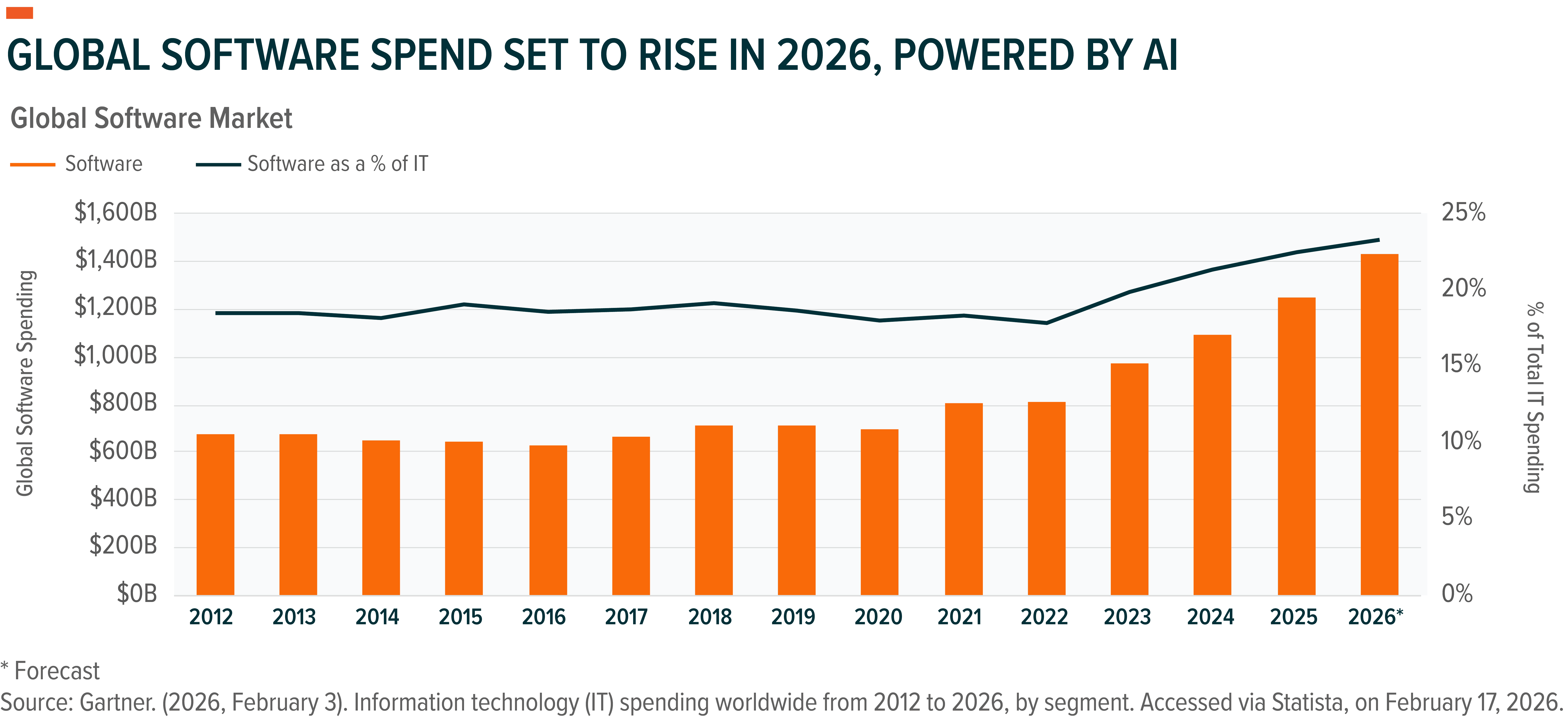

Stepping back from the recent volatility, enterprise budget line items tell a different story. Worldwide, IT spending is expected to reach $6 trillion, with software accounting for nearly $1.43 trillion – up 14.7% YoY (year-over-year). That puts software at roughly a bit over 23% of total IT spend, and still one of the fastest-growing major categories.6 Even more telling, GenAI model spending still implies ~80.8% growth in 2026, which means AI-related software is rapidly expanding even as the market debates disruption risk.7

Second, the broader AI buildout is still accelerating. Data center system spending is projected to approach $650 billion in 2026, with server spending projected to grow ~36.9% YoY.8 That level of infrastructure investment does not happen in isolation. It drives demand for orchestration, security, governance, monitoring, and developer tools – categories that directly support higher software spending. As AI CapEx keeps climbing, it’s difficult to see how the software ecosystem that supports it stays structurally weak.

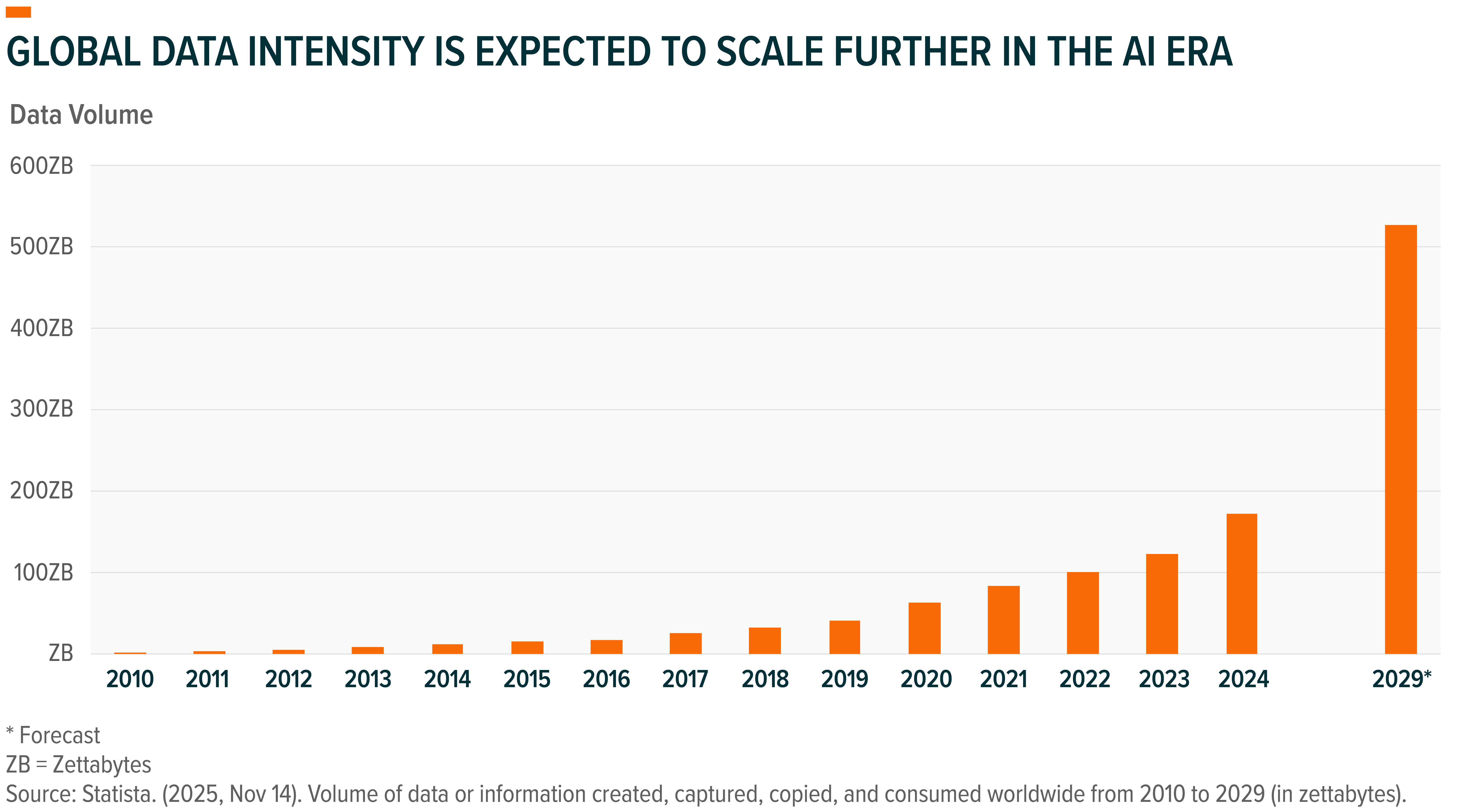

Third, software’s job has always been to translate rising data intensity into something operational: systems that store, secure, move, and interpret information. That underlying driver is not slowing. Global data created, consumed, and stored is expected to rise 254% – from ~149 zettabytes in 2024 to ~527 zettabytes by 2029.9 That surge reflects the sheer data intensity of AI. If that trajectory is directionally right, software spend is unlikely to compress while that happens.

Foundational Advantages in an AI-First Software World

Software has been through numerous disruptive cycles in the past. When the internet arrived, it moved software onto the web, made distribution instant, and triggered multiple waves of un-bundling and re-bundling that shifted power toward web-scale platforms (e.g., Netscape giving way to Internet Explorer, AltaVista giving way to Google Search, FrontPage/Dreamweaver giving way to WordPress).

Similarly, cloud computing rewired packaged software into pay-as-you-go subscriptions, rewarding vendors that could deliver continuous deployment and become deeply embedded in customer workflows (e.g. Siebel giving way to Salesforce, on-premise hosting shifting toward cloud hosted IT via AWS/Azure). Both cycles expanded the total market.

In the AI age, change is afoot again and while a lot remains fuzzy, we see three buckets where software should structurally thrive:

- Distribution Advantage: Vendors already embedded in core workflows can introduce AI features to their existing customer base without having to resell the product. That matters because AI features typically begin as augmentation, not replacement. The vendor that controls the workflow can bundle features, segment pricing, defend retention while competitors fight for attention at the edge. This is also where platform incumbency becomes powerful: most customers do not want multiple copilots – they want one that is deeply integrated into the systems they already use.

- Privileged Data Access: AI is only as useful as the context it can safely retrieve and act on. Software that sits on top of systems of record, or that has proprietary telemetry, has an advantage in building high-quality models and high-trust agentic behavior. This is not just about training data, it is about real-time enterprise data with permissions, audit trails, and governance. We believe the winners here are less likely to be “flashy AI apps” and more likely to be the companies that already access the pipes.

- AI Data Pipelines: As enterprises scale AI, the bottleneck shifts to execution and scaling – making tools for data preparation, code management, model evaluation, observability, and compliance, critical. In many cases, they are the prerequisites for moving from pilot to production. This layer may lack consumer visibility, but once AI becomes a strategic priority, we expect spending to gravitate toward the infrastructure required to run it reliably.

The common thread is that while AI lowers the cost of building features, it increases the importance of distribution, trusted data access, and operational control, while reinforcing the moat created by switching costs and deeply embedded workflows.

The tools most at risk are those that operate outside core workflows, lack trusted access to enterprise data, and fall short on reliability and security requirements.

Software-Heavy Themes We Like in the Age of AI

A broad, indiscriminate approach to software is unlikely to be effective in the years ahead. As AI reshapes the landscape, outcomes are likely to diverge across business models and use cases. Recent volatility has opened opportunities in areas of software that appear structurally aligned with enabling AI. Two categories stand out to us:

First is software that is exposed to AI Development. As AI CapEx rises, software vendors linked to deployment and the infrastructure stack that scales enterprise AI should see durable demand growth. This includes AI databases, data warehouses, enterprise search, observability tools, integration platforms, virtualization, and similar IT solutions. For example, in 2024, infrastructure software attracted roughly 30 cents in spending for every $1 spent on chips.10

Second, we also like Cybersecurity. AI expands attack surfaces, increases automated activity, and raises the value of identity, detection, and response. Even if broader software budgets get scrutinized, security tends to be where organizations reallocate rather than cut. Nearly 17% of all cyberattacks are expected to involve Gen AI by 2027.11 Emerging AI powered attacks are top concern for executives, gaining rapidly in recent years against other IT concerns.12

We have covered these areas at length in our recently published report: A Thematic Playbook to Invest in the AI Ecosystem.

Conclusion: Software Selloff Could Open AI Value Chain Opportunities

We believe AI’s impact on software is more targeted than broad-based, with pressure concentrated in seat-heavy models rather than across the entire sector. Enterprise purchasing decisions are still shaped by switching costs, implementation complexity, and data integration challenges. Platforms that embed AI directly into workflows, connect it to enterprise data, and manage governance and security are positioned differently from more replaceable tools. In this environment, broad sector exposure may miss that nuance.

A more focused, thematic approach – targeting the parts of the software stack that scale with AI usage and rising complexity – may better capture where durable demand is likely to concentrate.